After a bookstore event about my book Thank You, Anarchy with Rebecca Solnit on Saturday, some friends and I were joined at dinner by a young activist who’d been involved in Occupy San Francisco. We swapped stories of the movement’s past and ideas about its future. He talked about how he had considered himself an anarchist in the past, but wasn’t sure if he should anymore because he supports progressive and socialist electoral candidates. Then, as the check came for our dinner, he started talking approvingly about Rand and Ron Paul, figures normally associated with the exact opposite end of the political spectrum from anarchism. In particular — in no small part because of his identity as a Muslim — he appreciated their vocal opposition to U.S. drone strikes and wars abroad.

After two and a half years covering the Occupy movement, dating back to the meetings before the occupation began, his grab-bag politics didn’t faze me at all.

The role of the political right in the Occupy movement has become a matter of discussion again thanks to an article on “The Right Hand of Occupy Wall Street” by Spencer Sunshine of Political Research Associates. Journalist Arun Gupta, who helped found newspapers at several encampments and reported frequently on the movement, has responded at length. Sunshine purports to expose the role that certain right-wing groups — including libertarians, white supremacists and others — played in what was supposedly a left-wing movement.

Certain aspects of his account are uncontroversial. (Sunshine cites my book, in part, as evidence.) It’s true that individuals and groups associated with the far right became involved in the movement, or tried to co-opt it, such as with calls to “End the Fed.” However, he overstates particular impact they had in the movement’s primary decision-making processes. For instance, he points out that supporters of Lyndon LaRouche supported calls within Occupy for reinstating the Glass-Steagall act — but so did a lot more left-leaning Democrats, and even the initial Adbusters call that seeded the movement. Early on, too, traditional leftists like socialists and anarchists were generally reluctant to claim the movement wholly as its own. I believe that this was part of its strength; no existing political organization was strong enough in the fledgling Occupy organization to reign in its intuitive charisma.

Near the end Sunshine argues that, for Occupy Wall Street, “A more proactive first step would be to endorse an anti-oppression platform at the very start.” In fact, the brief Principles of Solidarity document passed by the OWS General Assembly included a point about “empowering one another against all forms of oppression.” Anti-oppression trainings were frequent, although optional. Throughout the course of the movement, strenuous attempts were made to create strong, enforceable community agreements to prevent oppression along dividing lines of race, gender identity, class and others. In certain sectors of the movement, these were effective. Most of the time, though — notably in the attempts to organize a Spokes Council decision-making structure — such attempts were run aground by people who were evidently intent on preventing anything constructive from taking place in the movement.

Near the end Sunshine argues that, for Occupy Wall Street, “A more proactive first step would be to endorse an anti-oppression platform at the very start.” In fact, the brief Principles of Solidarity document passed by the OWS General Assembly included a point about “empowering one another against all forms of oppression.” Anti-oppression trainings were frequent, although optional. Throughout the course of the movement, strenuous attempts were made to create strong, enforceable community agreements to prevent oppression along dividing lines of race, gender identity, class and others. In certain sectors of the movement, these were effective. Most of the time, though — notably in the attempts to organize a Spokes Council decision-making structure — such attempts were run aground by people who were evidently intent on preventing anything constructive from taking place in the movement.

Community agreements or not, however, what should a movement like Occupy do about someone like my dinner companion, a devoted and persistent activist with political orientations that don’t seem to map cleanly on the right or left?

It often strikes me that part of what makes grassroots resistance movements around the world powerful is their capacity to reveal the inadequacy of the usual political spectrum. What would the initial Tahrir Square uprising have been if either the secular liberals or Muslim Brotherhood members hadn’t been involved? Or the civil rights movement without either church folks or Black Panthers? These are sometimes unlikely and uncomfortable alliances, but they’re also what brings a movement the level of participation it needs to be effective — by revealing a hidden consensus that the ruling class doesn’t want anyone to see, the points of agreement that aren’t otherwise recognized.

Some of the right-wingers on the fringes of Occupy had nothing worthwhile to offer. The outright racists, certainly — though their presence was far less of a concern than unconscious racism among privileged leftists. Groups like organized libertarians and LaRouche supporters generally kept to themselves and handed out their literature from their own tables, and wouldn’t be seen elsewhere. But many individuals who had affinity with groups on the right became involved in Occupy for perfectly sensible reasons — because they believed in challenging the power of Wall Street and building power for the people. They might have disagreed with socialists or anarchists about how to do so, but the socialists and anarchists disagreed with each other about this, too. And not even Sunshine would claim that there was any meaningful presence of, say, mainstream pro-corporate Republicans, although there were plenty of mainstream liberal Democrats.

One of the things Occupy encampments like Liberty Plaza did best was serving as a school. Over the course of a week or two, I would see people’s political views transform in remarkable ways. These are the apocalypses — the unveilings, etymologically speaking — that I tried to capture in my reporting. People seemed to be experiencing the equivalent of a semester of school in just a day at Liberty not because of the much-touted consensus, but because of the debate and diversity. Mark Bray’s book Translating Anarchy clearly (and quantitatively) demonstrates that this movement radicalized participants and broadened their sense of political possibility. On the whole, it deepened their desire to build an intersectional movement led by affected communities, building power from the ground up.

The existence of certain obnoxious quarters of the right in Occupy was occasionally a problem for the movement, but the right’s presence was also a sign of Occupy’s promise. It was a reminder that discontent against corporate rule (and hope for a better way forward) is not limited to those who happen to be already socialized into leftist politics — a socialization not always readily available in the United States of America of the 21st century. It was a reminder that a movement against Wall Street can be big enough to win, though it might not be small enough to be pure. Organizers were correct to insist on opposing all forms of oppression early on; it was a shame that they didn’t develop the structures to enforce that commitment fairly and effectively. But if every inkling of the political right had been banished from the movement at the outset, there might not have been a movement at all.

It was all pretty confusing. But at Occupy San Francisco I tried to welcome all. But I wouldn’t put up with lies or hate.

Good piece. Glad you could visit SF. The Revolution never seems to end here.

Robert

Thanks for the comment! Yes, SF certainly has a certain corner on the revolution market, so to speak. It was quite life-giving to be there. Within a couple of hours I heard about revolution from a pair of techies, an old civil rights sit-in-er, a woman who believes Jesus is a bureaucrat in the Vatican, a weed-grower, and then some.

At least you would know that the avowed right-wingers were not agents provocateur (even if they might be provocative), as the intelligence community would have recruited ostensible leftists for that job.

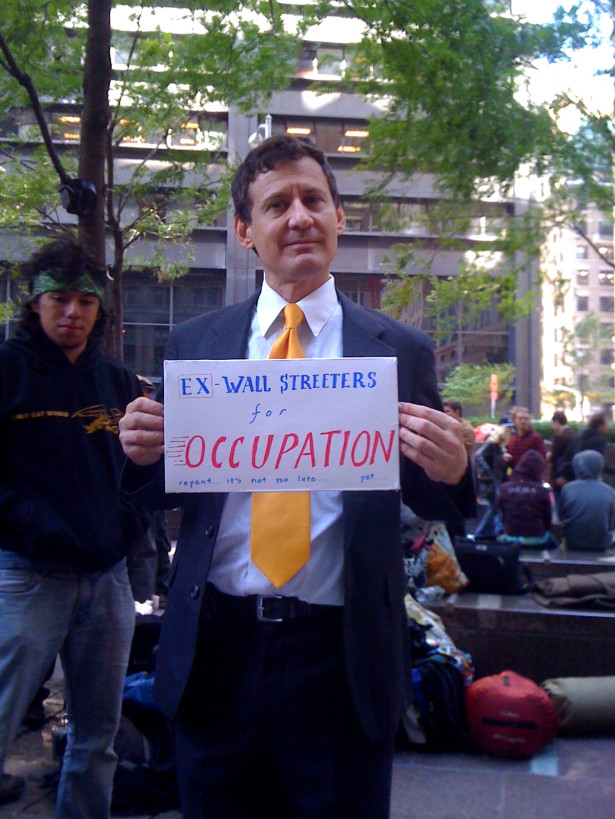

Great, so now I’m a poster boy for the right wing? I wonder why I wasn’t wearing my glasses in that photo.

Robert (there’s a trend to these comments…),

OWS Town Planning

Ha! Nice to hear from you, Robert! I know it’s not exactly accurate but was the closest thing I could find in the small collection of photos I have with me while traveling:)

Hey there, thanks for this piece. I agree with your conclusions but disagree with the foundational premise of the article, namely that a right-left political spectrum exists at all. Politics is far more complex than can be laid out in a single dimension, which is precisely the reason that so many people like your dinner companion were at OWS and other camps. Libertarians are not at all the opposite of anarchists. In keeping with the present discourse, Libertarians tend to be socially “liberal” while still fiscally “conservative”. And anarchists tend to be “liberal” on both counts. But obviously these two groups can find common ground at least on the social issues. I just wish that more people would see that the perpetuation of the mythical political dichotomy is counter productive and keeping us from talking about the issues that really matter. When there’s only a “right” and “left” or a “conservative” and “liberal” or a “rep” or “dem” then it also means that there’s always “us” versus “them”. But in reality, the “us” is 99%. So the infighting really doesn’t help! Plus, none of those terms adequately frame my worldview. While I do still call myself an Occupier, I will never associate that term any of the others. (See: politicalcompass.org)

Thanks for this. I’m not sure the left-right political spectrum is a “foundational premise” of the article so much as it is of the society that the article is speaking too — and as you see in it, I suggest that part of the truth movements have to offer is in revealing inadequacy of the spectrum.

“And anarchists tend to be “liberal” on both counts.”

NO.

two things:

1: I’d be interested in seeing the rebuttal from Gupta, but your link to that content is only accessible to people logged into facebook, and believe it or not, not everyone has an account or wants one. If you find his rebuttal valid, it might be more journalistic to quote from it and explain why his points are valid.

2: You say “Groups like organized libertarians and LaRouche supporters generally kept to themselves and handed out their literature from their own tables, and wouldn’t be seen elsewhere. ”

Do you think it’s unreasonable for me to read that as saying that you are ok with the reality that Occupy created a forum where right wing groups could recruit and spread their message to both the general public (which caused many to associate occupy with those groups) and young activists — and took no action to counter that?

1. Good point. I’ve just replaced the link with a Pastebin containing the discussion: http://pastebin.com/G2UmMTBb

2. It strikes me as fairly self-evident that a good society needs to find a balance between ensuring the right of all to free speech and protecting the basic rights of others. Occupiers struggled to reach this balance, and they didn’t always succeed. But many were reluctant to simply banish those they disagreed with, even if they sought to ensure oppressive voices could not hold sway in the movement’s decision-making process.

Also, the tables I’m referring to were often not even in the encampments themselves, but across the street or a block away — likely because of action that people in Occupy took to make clear that such messages were not welcome.

Occupy, although well intention, did succeed in developing leading issues on

the growing income gap and inequality driven by the structure of America’s

weakly unregulated economy. Yet, the movement failed due to dangerously undeveloped levels of political organization and leadership, rooted in the correspondingly unequal social/class dynamics of the Democratic/Corporate party. Thus, the mostly likely long-term outcome, now, will be in increase in social and political instability in the U.S., which will continue the corporate movement to export investment income to more politically stable countries, both rich and poor. Without a new center-left alignment in the U.S. it is doomed to become a weaker and less attractive place to live and invest.

Occupy is not more successful because too many people decided to sit on the sidelines and criticize instead of getting involved and changing the world.

The open organizing structure of Occupy means it is what the people who show up and do the work create.

Declaring Occupy dead or listing all of the things it did wrong is a waste of time. We have a world teetering on the brink of corporate slavery and ecological disaster. There is no time to attack people who are trying to fix it.

You don’t like Occupy? Anonymous is calling for a World Wide Wave of Action. A movement of Movements. Join or form a movement and help.

“We have a world teetering on the brink of corporate slavery and ecological disaster.”

Prove it! Charlatans, their victims and those with overly active imaginations have been forecasting doomsday since at least some of the “prophets” of the Old Testament some three-thousand years ago.

Neither assertion can be “proven,” except by waiting. These assertions are based on 40 years of studying history, science, math, political science, etc.

In my experience most people that are concerned with the success of occupy see a similar future threatening the world, and those are the people my comment was addressing.

If you are truly interested I can lay out arguments for why I think corporate slavery and ecological disaster are our current trajectory, but space in the comments section is limited.

I’m far less worried about the prospect of “corporate slavery” than the reality of government slavery. Of course corporations are a creation of government laws, so the real danger is from the government, and ridding the world of government would perforce solve the corporation problem. It is governments, not corporations, that wield the guns and the power to force you to do or not do certain things. Most folks are already enslaved by the state, which takes a large portion of their income and wealth every year or more frequently. And the U.S. fed gov retains the “authority” to force its subjects to fight and die for it–even the most pacifistic of subjects.

I am also more worried about global-warming or climate-change hysteria than about the earth warming or the climate continuing as it always has to change. The hysteria scares me because so many people are addicted to looking to government to solve their problems, and the rulers love the power it gives them when asked to solve big problems, that there is a chance that those complete buffoons in the nation’s legislature or at the U.N. will actually try to do something about the climate or the weather, which is guaranteed to result in disastrous unintended consequences.

I really don’t think folks need worry about corporate slavery while they are wearing the shackles with which the state holds them in subjugation.

Fully half of the U.S. armed forces in both Iraq and Afghanistan were supplied by private contractors. I call them mercenaries (many ex special forces trained by the US government for a $million each, by the way). Global corporations are heavily armed.

Corporations are now secretly writing the Trans Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. These two agreements would cover two thirds of the worlds countries. Among other things, they would give corporations the right to sue countries in international tribunals run by corporate lawyers, for profits they would have made, if regulations put in place through democratic processes would cost them money. (Who says children can’t work 100 hour weeks? Pay us the cost of not having child labor. Sounds crazy till it happens.)

Global corporations are becoming more powerful than countries (compare corporate balance sheets to GDPs of smaller countries) and if we don’t stop them, they will no longer have to worry about quaint ideas like “one person one vote.”

As far as climate change: Over the last decade every continent has experienced extreme droughts (part of the cause of the Arab Spring, combined with a bubble in commodity speculation). Regions of the world that have recently experienced their worst drought in 50 years include the U.S. West, Southwest, Midwest, and South East; then there is central China and Northern China, Russia, the Amazon, then Northern Brazil, all of Australia, the Horn of Africa…

If you don’t believe in science I can’t ever convince you, but if you do believe in science than stop listening to the tiny minority of oil industry paid “skeptics”and start listening to the at least 80% of actual climate scientists that say this is a real problem, and time is running out to stop it.

You and all your friends cannot do a single thing without resorting to violence–in which case youse guys would be squished like bugs–to impede those big bad corporations that you fear–except by resisting supporting the governments that make the laws that license governments. John, Do you pay taxes? If so, you are the problem.

@ “If you don’t believe in science I can’t ever convince you, but if you do believe in science than stop listening to the tiny minority of oil industry paid “skeptics”and start listening to the at least 80% of actual climate scientists that say this is a real problem, and time is running out to stop it.”

John, you are talking to yourself and you are a very confused person. What science are you talking about? I said I was more concerned with climate change hysteria than with climate change and you are living proof that I should be. Let us say that everything you believe about climate change and global warming is scientifically correct (which it is not, but that is beside the point.) And let us say that the earth is going to become uninhabitable because of whatever it is that the big bad oil companies are doing. So what? So what are you going to do about it? You see, John, I already know the answer. You are going to call on government to do something about it and the government will screw things up so bad in the process that you will soon be begging the big bad oil companies to save you from the government.

I’m not predicting doomsday or an uninhabitable planet, I’m predicting that under our current course, things will be a whole lot worse than they are now.

You seem to think you can just “end government” and all will be right with the world. Show me any time or place in the last ten thousand years that a large number of people lived for any length of time without government. I like to believe it is possible, but the only way it can happen is to slowly spread power outwards.

Iraq is a great experiment in ending government. We went there with enough force to take out Saddam and disband the police, military, and Bath Party workers, but not enough force to govern, and the result was 13 years of violent chaos and counting. Until humans find a way to create group structures that can mitigate internal violence and resist outside violence, the best alternative I see is to constantly refine government so that it does less and less damage, and helps people take more and more of their own power back.

Do you believe that pollution is changing the climate or not? Most people that actually do climate science think it does, and from what I know about math and science there arguments make a lot of sense. Am I going to wait for the fall of governments to do anything about it? No. I will protest directly against the polluters, but I will also try to get the government to not allow the use of public land, and eminent domain, for the purpose of releasing more fossil fuel into the air.

By the way market prices do not reflect the costs of pollution. When a kid gets asthma from breathing pollution, his treatment and loss of productivity and happiness is born by his family, not the oil company. This keeps the price of oil lower than the true cost, which means more is produced than would be if the price represented the cost. Economics 101.

If global warming raises sea levels, kills trees, and hurts farming, none of that will be reflected in the price of oil.

You really need to read a standard economics text.

Capitalism is actually very good and quite detailed at describing how markets work and how the internal structures (rules) create all sorts of incentives that have nothing to do with making people’s lives better (problems). The moneyed class and the politicians they invest in do a good job of sweeping them under the rug so that they can make mega profits using these distortions.

Yes government can also be used to manipulate markets, but markets themselves are plagued by lack of information, barriers to entry, economies of scale that lead to bargaining power imbalances between buyers and sellers, externalities like pollution or “public goods,” etc.

You can’t just wish away these structural problems with markets, just like you can’t wish away the fact that people use violence to control others.

@”Show me any time or place in the last ten thousand years that a large number of people lived for any length of time without government.”

Show me a time or place, prior to 1833 and the first fruits of the Abolition Movement, in the previous ten-thousand years what a large number of people lived for any length of time without slavery. Have faith; it can move mountains.

@”Until humans find a way to create group structures that can mitigate internal violence and resist outside violence, the best alternative I see is to constantly refine government so that it does less and less damage, and helps people take more and more of their own power back.”

You must read the book, DEATH BY GOVERNMENT, by R.J. Rommel, professor, University of Hawaii. He was the first and may remain the only person to ever investigate, document and compile the statistics on what he referred to as “democide,” the murder by governments of their own citizens and foreigners–not including combatants in wars perpetrated by governments. He compiled the statistics for the period 1900 to 1988. (He stopped compiling when the evidence and statistics became so gruesome and ugly that he needed a respite from the work.) As I recall for that 88-year period the grand total was at least 360 million victims. The very worst violence in the few short-lived periods of violence in the absence of a detectable government, including in such places as Iraq, Somalia, Syria, etc., finds fewer people slaughtered than under the auspices of some of the worst governments. John, your faith in government, though you insist it isn’t great, is nevertheless severely misplaced. Most of the “need for government” in people’s minds has been sown there and cultivated by–you guessed it–government propaganda. It is to your rulers great advantage that you think of government as you do.

@ “… the only way it can happen is to slowly spread power outwards.”

Lord Acton correctly observed that power corrupts. If it is power you seek, you will inevitable be corrupted by it whether you are inside or outside.

The abolitionist movement forced the government to end slavery, but it was the government that actually ended it.

Freeing slaves one at a time was not going to do it. The South had to get decimated in war to free its slaves.

Sad but true.

@”The abolitionist movement forced the government to end slavery, but it was the government that actually ended it.

Freeing slaves one at a time was not going to do it. The South had to get decimated in war to free its slaves. Sad but true.”

Not true, but a common mis-perception. By coincidence I am just now proofreading a draft of a forthcoming article by Carl Watner of http://voluntaryist.com/ explaining how slavery would be abolished by a voluntaryist society. Here is a quote from it by Jim Powell: “A peaceful, persistent, multi-strategy process of eroding slavery would have made it much less difficult to arrive at a point where blacks could both be emancipated and safe, flourishing with equal rights in a free society.”

The civil war may have removed chattel slavery, but because many Southerners were violently subdued by the North’s military war upon them they adamantly refused to recognize the former slaves as equals, and with the reins of government firmly in their hands after a short period of Reconstruction, the civil governments of the South dominated and oppressed the freed slaves for one-hundred years. Slavery was ultimately doomed by market forces. It would have ended without the Civil War, and it would have ended much sooner if the slaves themselves had adopted nonviolent resistance.

In England the nonviolent campaign of Thomas Clarkson and his mostly Quaker compatriots forced the government to pass the laws ending slavery. In truth, the law only confirmed that which the Abolition Movement had already persuaded the English population to demand of their government. Without government reluctance aided by pressure and money from the slave industry, slavery in England would have ended much earlier. You must read Adam Hochsfield’s BURY THE CHAINS to get an idea of how the British Parliament dragged its feet on the issue.

Nice analysis. I often think about the the two extreme ends of the political spectrum as meeting to form a circle. That is where the people most against any kind of government seem to be. And that seems to be where the right me Occupy.

There are important differences though. The anarchists at the extreme left care about other people and are for mutual aid and against using coercion. But the extreme right is all about the freedom to not help anybody for any reason, and think that the government should only be police and military.

My allies are anyone that believes in helping people and organizing for justice. Those that have no problem stepping over the hungry and the sick have a lot of growing to do, and are not my allies.

*Where the right meets Occupy*

Good article overall, but the author’s views are evidently based on several erroneous assumptions. Those don’t result in any real damage to the article’s purpose except to inhibit its clarity.

“Early on, too, traditional leftists like socialists and anarchists were generally reluctant to claim the movement wholly as its own.”

First let me say that the designations “right” and “left,” which, as I recall, derive from the seating arrangement in an assembly of French legislators, have meant so many different things to different people as to be far too ambiguous to afford anything like clarity or precision in writing or speaking. The above quotation is a good example. The author evidently places socialists and anarchists in the same leftist boat, whereas the two are as separate as, well, one’s right and left hands.

Anarchy, by the second definition in my Macbook dictionary is: “absence of government and absolute freedom of the individual, regarded as a political ideal.”

The same dictionary on socialism says this: “The term ‘socialism’ has been used to describe positions as far apart as anarchism, Soviet state communism, and social democracy; however, it necessarily implies an opposition to the untrammeled workings of the economic market.The socialist parties that have arisen in most European countries from the late 19th century have generally tended toward social democracy.”

Socialists and anarchists do not fit into the same “leftist” category. They may have made common cause in the Occupy movement, but their ultimate objectives are definitely at cross purposes. (I do agree with the author’s point that there are advantages in opposites finding common cause in challenging an oppressive status quo.)

Socialists, of whatever variety you choose, including “libertarian socialism,” “voluntary socialism,” anarchosocialism,” “horizontal socialism,” or what have you, all recognize the necessity of government force (viz., violence) to achieve the objective of dispossessing the current owners of the means of production of their productive resources. All socialists, whether they admit it or not, are dependent upon government force to achieve their objective of common ownership of the means of production. And, as the dictionary stresses, socialism “necessarily implies an opposition to the untrammeled workings of the economic market,” which is to say the free market.

Anarchists, on the other hand, want to eliminate the state or deprive it of its so-called “authority” to initiate violence, and then let the chips fall as they may. The way the chips are bound to fall in an environment of freedom where there is no violent State to work its oppression is into the “hands” of laissez faire–the free market. Socialism was essentially elaborated by its originators and promulgated by its champions as a means of suppressing the free market, which is to say suppressing freedom. To do that, it needs the state, and thus socialism is as far removed from anarchy as one can go.

Again from the article: “Sunshine purports to expose the role that certain right-wing groups — including libertarians, white supremacists and others — played in what was supposedly a left-wing movement.”

This is another example of the foggy thinking that the left-right dichotomy allows–if it doesn’t actually promote it. Libertarians in their philosophy are are as far from white supremacists as progressives are from neoconservatives. Yes, yes, I know, (presumed) libertarians Ron Paul, F.A. Hayek and Murray Rothbard, have been accused, generally by socialists, of associating with all sorts of discredited reprobates, but that obviously cannot taint their philosophies any more than the fact that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Party’s formal name was the National SOCIALIST Party means that socialist Norman Chomsky is a fascist who embraces the likes of Mussolini. Guilt by association is a nasty, underhanded gambit.

Excuse me, Mr. Noam Chomsky. I knew that, but had a Freudian slip, perhaps because Norman was one of my father’s chosen names.

Good points. Except, without government force, roving bands of marauders would probably not let any markets function at all. The human race has a lot of maturing and maybe evolving to do before violence is not the way a brutal minority imposes its will on everyone else and simply taking down governments won’t change that.

The inevitable concentration of power that comes with using force to put “production in the hands of the workers,” is equally unlikely to result in the future most socialists have in mind.

And the manipulation of markets, that the internal rules of capitalism fosters, obviously concentrates power in a way that should be described as mega-larceny.

This is why I would like to see everyone that cares what happens to others to drop their beloved labels, come together, and invent something new that combines the best of all systems.

This was what I, and I think a lot of occupiers, were aiming at (although many are hostile to capitalism) and why the movement was so open ended.

But of course this is quite a tall order, so many with shorter term goals were frustrated.

I have to add that the main technique of the .1% is to divide and conquer, so pushing the idea of a one dimensional spectrum, where anyone who is not a pro-corporate “centrist” is a wackjob extremist creates all sorts of reasons for the rest of us to fight.

Nonviolence is many times more powerful than violence, and more efficacious as a means of security than force. The reason that violent people have succeeded in using violence to dominate others is because the others replied to with violence themselves. Violence will never defeat violence.

What are the “internal rules of capitalism?” Because capitalism has been confused by many with corporatism and fascism, I don’t defend it, but rather defend laissez faire, free markets and freedom. I ask, what is it you don’t like about freedom. I have been studying the principles of liberty for over 50 years, if that means anything and I don’t think it does. But from my limited knowledge of liberty I am convinced the the state, with its monopoly on violence is the fountain of almost everything people object to in this world. There will always be bad guys, but when the bad guys grab the reins of governments people die by the hundreds of millions or more each century.

I think if you will study the principles of the free market as elaborated by such men as Austrian Economist Ludwig von Mises, particularly in his magnum opus, HUMAN ACTION, you will see that the system you long to see invented is the free market, and without introducing violence into the equation there may logically be no other imaginable alternative. If you ever hear of one, please let me know, but I’ve been looking into this for some time, seen many proposed “new” ways of organizing society, but nothing, but nothing seems able to compete with freedom without planning or organizing–except on an individual and group level.

Corporations are a curse, and a violation of the principles of free markets and freedom, which require personal responsibility, but the laws of the State that create corporations endows them with “limited liability,” which removes the responsibility factor from the equation.

Markets rely on contracts and contracts rely on force to enforce them. (Again I am hopeful that there may be a better way, but its going to be a lot harder than “end government” and let markets run free.)

If you take the police away than I can come to your store with my gun and take your stuff for free (not that it never happens now.)

Government is made by people who want to leave their victims productive, so they can come back tomorrow and take some more. And they “protect” you from other thugs because they don’t like to share.

Over time systems of laws are developed to make them even more productive and markets are regulated so that they actually function. A market without regulation is like a car without brakes or a steering wheel. I mean I’m a big fan of Adam Smith and the invisible hand, but he was still talking about markets with rules.

The problem with taking down a government with nothing to replace it, is that the resulting power vacuum is not filled by perfectly functioning free markets that make everyone free, but by some other group of thugs (See the Ukraine for example, or Iraq, Ethiopia, etc.)

The internal problems with markets can be found in many standard capitalist textbooks. Externalities, oligopoly or oligopsony (e.g. many more sellers of labor than buyers) and other imbalances of power brought on by efficiencies of scale, manipulations, bad regulations, etc.

In a perfect market, there are no profits, because if you raise your price above the market price, someone will undersell you. Of course there are no perfect markets, so there will be some profits. But obscene profits are evidence of broken markets. When the accumulated profits of 85 people is equal to those of half of the earth’s population, especially after decades of de-regulation, it is not only government that is the problem. If markets worked as well as people wish they did, governments would be powerless to screw them up (see the Drug War) but the internal forces of markets make it most profitable to cheat, which after a while crashes the market.

Customary rules of conduct have been around and worked well without the aid of government force since the dawn of civilization.

@ “If you take the police away than I can come to your store with my gun and take your stuff for free (not that it never happens now.)”

You can do so now and I promise I wont call the cops, but here’s betting you wont–and if you wont there are a sufficient number of others just like you who wont to keep me in business and keep me prosperous and my customers happy, and if a thug does come along there a lots of ways without the cops to frighten the poor fellow away including the assistance of those happy customers of mine–like you. We don’t need government to steal from us to prevent others from stealing from us.

@ “The internal problems with markets can be found in many standard capitalist textbooks. Externalities, oligopoly or oligopsony (e.g. many more sellers of labor than buyers) and other imbalances of power brought on by efficiencies of scale, manipulations, bad regulations, etc.”

I asked you “what internal rules.” You reply with “internal problems.” You didn’t answer my question. Furthermore, none of the problems you raise are endemic to free markets. Rather they are either fictitious, or they are caused by governments intervening in the market. You must read Mises Human Action if you are going to ever get a good understanding of economics, which is vital to understanding how the world really works and to save you from being taken in by a lot of b.s. I never read “capitalist” text books. I confine my study to real economics, which is to say Austrian economics. Your comments on markets reflects a profound degree of misunderstanding, which you could clear up by reading Mises.

I do agree that nonviolence is more powerful than violence in the big picture and hope that we can get everyone to agree to that soon. But that is little consolation while you are bleeding out watching your family get murdered or worse. This is why I do believe in self defense, but not as an excuse to be aggressive, like: “Your ideas are a threat to my way of life so I will kill you and burn your books,” that is practiced by many in this world.

John, you may not believe me, but an unequivocal, unwavering commitment to practicing nonviolence even in the face of violent aggression is the single most efficacious means at your disposal to keep you and yours safe from all harm. Violence begets violence and will never serve to defeat it.

I admire your bravery.

The idea that Occupy’s political diversity was a sign of its strength is naive. It was more a sign of its political immaturity. The right wing often expresses opposition to corporate rule in the infancy of movements like Occupy, but usually ends up asserting the corporation’s right to rule under the guise of the “free market.”

“The Right Hand of Occupy Wall Street” by Spencer Sunshine brings an issue that was very worrisome, for some; rightist elements were certainly present from the start. The defensive and dismissive reactions against the article as some kind of smear campaign are symptomatic of a major flaw in the ‘movement’, i.e., the hostility to consider well-intentioned and important criticism. The result of this lack of reflection is further illustrated in articles and books that flourished as mushrooms, some of which would sell as Hollywood scripts, but as such they portray reality distortion.

It seems self-righteous to state, as Nathan and others do, that the impact of those right elements and the lack of a more clear political definition in the ‘movement’ had minor consequences, while at the same time prioritizing charisma (using Nathan’s word) and populist slogans (99%) over substantial politics. It should be no surprise that paramount collectives as immigrants, African Americans, Native Americans and others on the receiving side of oppression had little to no appeal to join. To grow in numbers and politically was difficult in this environment.

I didn’t get involved, at least initially, as an anarchist because the whole thing was really urban centric and didn’t appeal to me living and organizing in rural PA, not because we weren’t “strong enough” in this area. The presentation of filthy dreadlocked privileged white protesters who wiggle their fingers and camped in the cold weather on the news is exactly the kind of thing that makes people averse to participating in mass protest movements around here. It’s simply, “I agree with those Occupiers, but I’m not like them” which is an enormous cultural barrier. Back then, I posted and re-posted this article on inessential weirdness in organizing which is really important: http://www.classmatters.org/2006_07/its-not-them.php

It wasn’t that anarchists in this area weren’t strong enough or capable enough to stay involved in important roles, I think anarchists, particularly those of us with organizing training and experience, saw Occupy as a hopeless mission with no willingness to run campaigns, make strategic goals, and win concrete improvements in people’s lives. When I did get involved, we were doing anti-fracking actions as “Occupy Well Street”, picketing with laid off firefighters in Scranton to get their jobs back, providing DA trainings, and facilitating meetings better. However, there wasn’t enough early notice or support for us to drop what we were organizing (winning EPA water deliveries to people living in a designated Superfund zone) to fight for our right to camp in the snow outside a stretch of bars in Scranton that subjected us to regular harassment, theft, and airborne beer bottles.

Occupy also was planned right before an intensely cold winter and it snowed on Halloween, so it was a tactical nightmare. The whole thing, in my opinion, set back the reputation of organizers in our communities here because people think we’re like those “Occupiers” who just sit around at drum circles taking tinctures. TBH, thinking back, I remember a kind of cultural imperialism by punks, urban liberals, and hippy dippy people in the movement that made it really difficult to pretend that Occupy was inclusive of the more redneck, rough and tough, culture you find in and around Scranton.

It’s not like rural people and rednecks weren’t present in cities at Occupy actions, but urban organizers, who, in my experience, are largely oblivious to rural cultures, failed to lift up the fact that farmers, pipeliners, conservative military families concerned about the VA cuts, hicks, hill billies, and rednecks were in their midst, making the media presentations online, in the newspapers, and on TV largely irrelevant to our lives here. Many people from two and three hours away from any city traveled to be a part of Occupy camps and actions, but little support is ever sent our way, I think, because there’s a pompous attitude among urban organizers that any important action takes place in cities, outside office buildings, surrounded by cops. Even small town natives who moved to their respective Bay Area and Brooklyn bastions of progressive thought downplay the role their hometowns must play in any kind of revolutionary social movement…so rural anarchists are left here organizing with few hands and a lot of ground to cover.

I don’t (or rarely) go to actions or protests in cities anymore because of that…it’s a waste of my time when I could be here organizing. We also only have two police officers on duty in a few hundred square mile area…so direct actions are a lot easier to pull off and rarely end in police violence, and usually without arrests (if the police even bother to show up).

John McGloin posted the following comment, but there was no button to reply to it so I post his comment here in its entirety and respond to it.

John wrote: “Do you believe that pollution is changing the climate or not? Most people that actually do climate science think it does, and from what I know about math and science there arguments make a lot of sense. Am I going to wait for the fall of governments to do anything about it? No. I will protest directly against the polluters, but I will also try to get the government to not allow the use of public land, and eminent domain, for the purpose of releasing more fossil fuel into the air. By the way market prices do not reflect the costs of pollution. When a kid gets asthma from breathing pollution, his treatment and loss of productivity and happiness is born by his family, not the oil company. This keeps the price of oil lower than the true cost, which means more is produced than would be if the price represented the cost. Economics 101. If global warming raises sea levels, kills trees, and hurts farming, none of that will be reflected in the price of oil.”

John, of course pollution is changing the climate. Everybody knows that. And the sources of pollution include coal-fired power plants and active volcanoes. But the point I have been trying to get across to you is that climate-change hysteria, a phenomena most prevalent among political “progressives” and others who practice Statolatry and worship at the alter of the state, is more dangerous than climate change because if those affected with climate-change histrionics can scare enough people into pushing governments to “just do something” about climate change, their efforts will open the door to the most massive government spending in the history of government, for there can be no larger challenge to politicians than changing the earth’s environment itself. And of course much of the spending will be directed to their minions and rub off on themselves. Is that what you want? Are you out to get a share in the lucre of government climate change spending? I doubt if you are, but you may rest assured that many of your compatriots afflicted with climate-change hysteria want exactly that.

John, you say, “By the way market prices do not reflect the costs of pollution. When a kid gets asthma from breathing pollution, his treatment and loss of productivity and happiness is born by his family, not the oil company. ”

Tell me something I didn’t know when you were probably still in diapers. But what you don’t know is that the “market prices” are not FREE market prices, but the prices of markets heavily impacted by government legislation. A truly free market would fully reflect the so called “externalities” that statists like to blame on free markets when in fact the problem is the statist’s governments own doing. Why are the corporations that pollute not made to pay for little Sally’s and Johnny’s asthma? Answer: the rule of law–not the immutable laws of the free market. You continue to ignore the fact that I have shoved in your face several times that corporations and their limited accountability for their actions are devised and implemented by the statist’s government’s rule of law.

John, you say, “Economics 101. If global warming raises sea levels, kills trees, and hurts farming, none of that will be reflected in the price of oil.”

Economics 512. The FREE market, not the pseudo market you are referring to, is capable of and will fully reflect–and undoubtedly mitigate–the government-induced externalities you are pointing out. If you had any interest in mitigating the effects of global warming you would work to end government not pander to it for global-warming legislation. Take a break, John. You evidently learned your Econ 101 from a school that used Samuelson’s text book, which is one step up from Marx’s brief incursion into economics with Das Kapital.

There is no government in the scenario involving the oil co. that gives the kid asthma. No government forced the co. to produce oil. or forced their customers to burn it. Nor did the government prevent the oil company from paying for the medical care or the days of school missed.

There is no cause and effect in your analysis. You just randomly blame government for everything bad in markets or otherwise and wish them out of existence.

If you could snap your fingers and send home all of NYC law enforcement you would not get “free markets.”

Heavily armed gangs would roam the streets taking advantage of the power vacuum. Stores would pull down their gates and the markets would close. The gangs would break in, take what they wanted and sell the rest. They would take slaves and set up palaces in the biggest mansions they could steal.

Then, as boundaries between them developed they would start calling themselves the government. If they were smart enough they would let the stores reopen and force them to pay for protection.

And those that resisted violently or not would have their heads placed on pikes in the street, just like governments have done for 10,000 years.

It has taken a long time to tame governments so that they don’t respond to criticism with automatic murder. It will take a lot longer to wind them down so that they don’t murder at all.

If you know a short cut I’d love to hear it. But free markets ain’t it.

John, you appear to me to be a dyed-in-the-wool statist whose religion is Statolatry and who worships at the alter of the almighty State. I give up. Keep embracing your violent State, but don’t think you are an anarchist. Keep imbibing the State’s doctrine of domination while pretending to be free. Keep paying your taxes to support your State’s wars and domination, and keep collecting your welfare benefits derived from OPM (viz., sounds like opium, is equally addicting, stands for other people’s money–forcibly taken.)

I don’t think of myself as a “statist,” but it’s true I have not been convinced that there is yet a viable alternative. I am still trying to help create one anyway. Or at least reduce the damage done by states, and increase the good.

It’s very easy for people that don’t want to pay taxes to claim that every problem with market economies are caused by the state (even in situations when governments are not involved) because there is no place that governments don’t exist so we can’t prove the negative.

But just because you don’t pay taxes doesn’t mean you don’t benefit from the state. I’m guessing you use the roads that the state builds (with my money) and I bet if your house was burning you wouldn’t chase away the fire department. Think a bit and you will find other ways you benefit from the taxes you don’t pay.

I never claimed to be an anarchist. But I have to say I’ve never met an anarchist who worried about “other people’s money,” or that thought “FREE markets” were the answer to everything. That was always more of a right wing libertarian thing. Maybe that original article wasn’t so far off.

John, Everybody pays taxes, even those who would resist if they could, for many taxes are collected so surreptitiously that the victim is unaware of paying. Such would be an excise tax paid by an importer on a good produced abroad. Such taxes included in the price of a good are completely invisible to the purchaser. Other taxes are virtually impossible to avoid, such as sales taxes and the tax on gasoline–which cannot be avoided unless you make your own. Anyone who uses the roads in a gas powered vehicle pays for the roads. But being forced to pay (yes forced, because if a gas station doesn’t collect and pay the gasoline tax, the owner will be sent to prison and killed if necessary to accomplish capture) isn’t something I could ever be proud of as you seem to be. And even if I was able to avoid every tax, rest assured that I would not be “benefiting” by using the roads that others pay for because they are forced to pay. If I had a choice I would use private roads, but the government doesn’t allow competition. There is no benefit when a persons is deprived of their freedom to choose by an enforced government monopoly.

John, government is nothing and could not exist if it didn’t resort to initiating or threatening to use force–violence–to accomplish its objective. Every anarchist I know objects to government on the grounds that it is wrong to initiate force to accomplish one’s objectives. Government depends on taxation, which is stealing. There is no distinction whatsoever between taxation and extortion, except the government immunizes its collectors from prosecution for extorting their victims. You pay taxes for one of only two reasons–either you don’t know how to avoid paying, or you are compelled by fear of your government to pay. Furthermore, you refuse to take responsibility for the violence, rapine and murder of innocent people committed by government agents supported by your taxes.

John, you wrote: “There is no government in the scenario involving the oil co. that gives the kid asthma. No government forced the co. to produce oil. or forced their customers to burn it. Nor did the government prevent the oil company from paying for the medical care or the days of school missed.”

You are deluding yourself to avoid your own part in the oil company’s malfeasance. Your government through its laws and with your taxes created, licensed and sanctioned the oil company’s malfeasance. Without the grant of limited liability to protect it from full responsibility for its misdeeds, that kid with asthma for whom you shed crocodile tears would not have asthma. Please remember this: corporations that do harm are created by government laws. When you remove responsibility for one’s actions from the equation by granting limited liability, you invite malfeasance. It is true that the government doesn’t make anyone do harm (other than its agents), but when people are freed by government from responsibility for their actions, human nature assures that some people will take advantage of that illicit “freedom.” The oil company’s malfeasance and their customers’ who burn the oil and pollute the environment are acting exactly as you do when your government’s agents commit atrocities, which you refuse to accept as your own.

I explained early on that all governments are basically gangs selling “protection.” I just think that some protection rackets are better than others, and if I’m going to have to live under one, I’d rather live under one with a constitution, where most of the censorship and repression is self imposed and enforced by media manipulation, and not as often imposed by sticking activists heads on pikes. I don’t see an instantaneous path to a gang free world, so I work from inside and outside the system to make it more responsive to democracy.

I don’t even see how you support democracy, since in a market $1 = one vote, instead of democracy where one person should equal one vote.

If there was no government, the oil company would not have to be a corporation, but it could still set up shop on the land near where you live and dump pollution on your house. Then what would you do about it? What would the asthma kid do about that? What would prevent them from putting a pipeline down your private street or fracking next to your well?

Your magical FREE market has no remedy for these situations because they all let the oil company shift the cost of its pollution on to third parties, so it can sell at a lower price, which raises the demand, creating more pollution.

John wrote (below): “I don’t even see how you support democracy, since in a market $1 = one vote, instead of democracy where one person should equal one vote.”

Where did you ever get the idea that I support democracy??? Democracy is mob rule and at least as dangerous to individual liberty as any dictatorship, maybe more so because when people fool themselves into thinking that by voting they become the rulers–they don’t, they just think so, the real rulers are the politicians they elect and the agents the politicians hire or draft to their service–they can be just as arrogant, stupid and demented as the worst of the Caesars. I don’t support any form of government, and neither should you because you wont take responsibility for the many nefarious actions of YOUR government.

John, I can’t tell you how far from the truth you comments about the free market are. You are simply repeating the ridiculous charges that socialists and other statists have levied against the free market beginning with Karl Marx and continuing to this day by the likes of Paul Krugman in the New York Times. I implore you to look into the works of Ludwig von Mises. You have nothing to lose, except your parodic view of laissez faire and your illogical support of statism–even though you admit it is a gang of thieves.

“Where did you ever get the idea that I support democracy??? Democracy is mob rule and at least as dangerous to individual liberty as any dictatorship.” -Ned Netterville

Now we’re getting somewhere. What about consensus? HOw do you think consensus works and do you think that is how decisions can be made?

So you are OK with the $1 = 1 vote paradigm. What happens when a small group of people control 80% of the money and 80% of the decisions, don’t they just use that power to amass more wealth and power? What is to stop them from hiring private armies to steal another 19% of the wealth and enslaving the rest of the population? What mechanisms in your free market prevents this.

What happens when some people can’t afford food, housing or healthcare?

From what I can see of human history we started out with a free market and ended up with empire. What went wrong?

John, I meant to include this in my comment referencing the books by Mises and Hoppe. It is from an article at Mises. org:

“However, this is not a dispute about heuristic questions, but a controversy concerning the foundations of economics. The mathematical method must be rejected not only on account of its barrenness. It is an entirely vicious method, starting from false assumptions and leading to fallacious inferences. Its syllogisms are not only sterile; they divert the mind from the study of the real problems and distort the relations between the various phenomena.”–Mises http://mises.org/daily/3540

Now, on to your defense of democracy:

Democracy is not consensus. According to my Apple dictionary, consensus is “general agreement : a consensus of opinion among judges | [as adj. ] a consensus view.” Democracy is “a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.” Quite different, I think. If I am part of a consensus of several or many people, I am in agreement with whatever it the consensus has concluded. If I am not part of a consensus, as long as government isn’t involved it is unlikely to be of any concern to me. Democratic government, on the other hand, can force me to do what the majority wants even if it violates my morality to do so. Democracy is government, and government is evil because it depends on the initiation of force against inoffensive people, if for no other reason than to tax their resources for the purpose of funding it and paying the rulers.

John McGloin suggest to me: “You really need to read a standard economics text.”

John, what “standard economics test” that you have read would you recommend?

From what I read in your comments, particularly regarding markets and externalities, you may have read a little from Paul Samuelson’s egregiously bad text–but little else beyond that.

Here’s a few I’ve read:

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

Microeconomics Theory and Applications, Dominick Salvatore

Macroeconomics, N. Gregory Mankiw

Macroeconomics Principles, Problems and Policies, Campbell R. McConnell and Stanley L. Bruce

Public Finance, Harvey S. Rosen

Using Econometrics, A.H. Studenmund (not really an economics book, but useful for understanding statistical arguments. My best stats teacher kept reminding us, “it is not hard to fool others with statistics, but be careful not to fool yourself.”

John, very good. Unfortunately, from my perspective, except for Smith’s W/N, none of those books deals with economic science–the science of human action. Statistics, macro economics and mathematical economics are not part of the science of human action–viz., economics. Human actions cannot be measured by means of statistical analysis. This, of course, opens a huge debate on what is or isn’t economics which has been going on ever since J.M. Keynes claimed (falsely) in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money to have refuted Say’s Law and essentially overthrown the methodology of classical economics. The difference is essentially one of methodology: Keynesianism and its many permutations being essentially empirical versus the a priori method of the classical economists and today the so-called Austrian school. When I was in college Keynesian economics such as you consider economics ruled the day and virtually every college course in economics. Indeed, “macro” economics isn’t even a part of Austrian econ. It was only in the years after I graduated that I came across some of the writings of the Austrian economists and my eyes were opened. I can only suggest that you read something from Austrian-school economics, and I most especially recommend something by Ludwig von Mises in order to understand the vast difference between the two schools of thought.

I will read some Ludwig, but standard textbook economics is not based on statistics, although some times statistical methods are used to compare it’s predictions in the real world.

Market economics is posits that humans get utility from products and services, and builds mathematical models from that assumption, informed by human behavior.

For example, you would get a lot of utility from owning one car, but the utility from owning a second car would be less, and the more cars you own, the less utility you get from each new car. Thus you get decreasing demand curve.

Another example, as price goes up people want to sell more, but buy less, so the market price should be where demand = supply. It’s mathematical models that make sense with how people make decisions, on average.

Another example. The production of many goods can be made more efficiently by having a large operation making many units. As long as the cost of making the next unit is cheaper than the last unit, it makes sense to grow your operation. For some goods this results in very few firms dominating the market. This gives those firms an advantage in negotiations, which pushes up the price above what the market price would be without that advantage, increasing profits, but reducing supply. It is all very logical and although arguments can be on specifics, not randomly generated.

@ “Another example, as price goes up people want to sell more, but buy less, so the market price should be where demand = supply. It’s mathematical models that make sense with how people make decisions, on average”

John, that is a good example of economic thinking, but using a mathematical formula adds nothing whatsoever to what you said, and math modeling has never added anything but ease of confusing matters to economics.

Mises HUMAN ACTION is not an easy read; I had to read a few parts of it two and three times before I was able to fully grasp, although most of it wasn’t that hard, but if you have the gumption to tackle it, I believe you will come away with a new and exciting understanding of economics, and a whole new perspective on human action as well as an appreciation for the immense value of a priori reasoning versus the empirical method for understanding how the world works. The empirical method is fine for physics and chemistry but useless for economics, logic and mathematics. You will see–if you tackle Mises.

The example you give in your last paragraph is actually an example of a priori economic reasoning. Unfortunately it isn’t careful enough for you have overlook some necessary and logical considerations that leave your conclusions regarding the skewed market price of goods produced by firms that dominate the market for a particular good subject to being easily refuted. I wont go into it here, but rather leave it for you to read Mises, except to say that the conclusion you arrive at couldn’t transpire under a free-market regimen.

I started reading Mises, but I think you need to actually learn about the mathematical models, because they are quite detailed, make a lot of sense, and shed light on the relationships between variables in human transactions. They are models that firms use daily to make decisions.

I do question some of the assumptions behind the models, and think that many people that use them to their advantage like to ignore the parts that would make them less rich, but I really don’t think you can get a full picture of economics without them.

And I don’t think that you can ignore empirical data either. Every theory should be checked against data. Adam Smith used reams of data to arrive at and support his theories.

Another example: I have written a few papers on the drug war, and an important aspect of that problem is the elasticity of demand (the slope of the demand curve). Since, people are willing to pay a much higher price to maintain their supply if necessary, the demand is inelastic (steep slope) so that interdiction actually makes the business more profitable. I found a quite detailed dynamic model of the cocaine trade which used actual drug prices to set the coefficients and agrees with this theory. The model also pointed out that if you interdict the money going back to the dealers it hurts them very much, but of course they use the same banks to launder their money as arms traffickers and the CIA, so the government puts few resources into that.

All kinds of analysis is necessary. Otherwise you have a small part of the picture.

The revolution = love.

This is in response to John McGloin’s comment, which follows this posting.

John, Two books that best elaborate the methodology of Austrian economics and the weakness of the empirical method in economics, the science of human action.

Economic Science and the Austrian Method

Hans-Herman Hoppe

Entire Text in PDF

Preface

Praxeology and Economic Science:

Sec I : “It is well-known that Austrians disagree strongly with other schools of economic thought…”

Sec II : “Non-praxeological schools of thought mistakenly believe that relationships between certain events are well-established empirical laws…”

On Praxeology and the Praxeological Foundation of Epistemology

Sec I : “As have most great and innovative economists, Ludwig von Mises intensively and repeatedly analyzed the problem of the logical status of economic propositions…”

Sec II : “Let me turn to Mises’s solution…”

Sec III : “I shall now turn to my second goal: the explanation of why and how praxeology also provides the foundation for epistemology…”

Sec IV : “In so establishing the place of praxeology proper, I have come full circle in outlining the system of rationalist philosophy as ultimately grounded in the action axiom…”

Found at:–http://mises.org/esandtam.asp

John, this is a small book and is available for downloading in PDF free of charge.

The other book, also short and available on the web is Mises’ THE ULTIMATE FOUNDATION OF ECONOMIC SCIENCE. Here is the URL for the download: http://mises.org/document/120/Ultimate-Foundation-of-Economic-Science-The

Here is a review from that same link:

There are two senses in which this book is indeed ultimate: it deals with the very core of economics as a science, and it is the last book that he wrote. For that reason, it is a real milestone in the history of the Misesian oeuvre that this book is newly available in this beautiful new hardbound edition.

If you have never read this book, you will be struck by the fiery and determine prose and the weightiness of the subject matter…The content reflects a lifetime of learning and his desire to make one last impassioned statement to save both economics and liberty from sure destruction at the hands of intellectual error.

As his career was coming to a close, Mises saw that that fiercest battles over economic questions come down to issues of epistemology: how do we determine what is and what is not true in economics? How do we even know that economics is a valid science? What are the methods we should use in studying economics? What constitutes a true proposition and how do we know?

These questions matter because, as Mises says, the very future of freedom and civilization itself depend on economic science, the development and application of which was “the most spectacular event of modern history.”

Between Mises’s earliest writings on this subject and this book, two movements had taken hold: “scientific” planning in public policy, and positivism in the social sciences. Mises here battles both, first by showing how the two are related, and, second, by demolishing the basis of both. He shows that humans cannot be studied in the same way that we study the physical world. We are dealing with volitional beings whose choices make controlled experiments completely impossible.

And yet does that imply that a kind of chaos exists in economic theory, that we must throw up our hands and do nothing observe that all is in flux? Not at all, says Mises. There is a logical structure of the human mind that manifests itself in economic reality through strict laws of cause and effect. To understand economics is to see these laws as universal and inviolable.

I want to post the following here in hopes John McGloin will read it:

My Look Inside the United Nations

Life is a lot more entertaining with cool friends.

In 1999, my friend Henry Lamb mentioned that he had been attending UN meetings. I thought it sounded intriguing and asked for details. After all, reading about an organization is one thing; actually attending its meetings is another. And because I was so enthused, Henry offered to get me in to the Kyoto accord meetings in Bonn, Germany.

I had preconceptions about the United Nations, of course, but I was looking forward to seeing the real thing in person; only then would I know if my guesses had been correct. So, I made my plans.

Arrival

The meetings were held in a magnificent hotel, surrounded by hundreds of soldiers and policemen. Everything was absolutely first class. To this day I don’t think I’ve seen its equal in terms of high-end, well-run meetings. Everything was pristine; every need had been considered and addressed in advance.

There were several days of meetings scheduled, some in smaller meeting rooms and others in the big auditorium, complete with language-specific headphones and a bank of professional translators. Again, absolutely first class.

On the second floor of the facility was a huge computer room. There must have been fifty terminals available. The connections were excellent (especially for 1999), and there were always open machines. This was a courtesy, not only for the participants, but especially for the press.

The attendees, as you might suspect, were all well-dressed, and all appeared to be feeling special about attending such impressive, elite meetings. I, on the other hand, had a bit of a Groucho Marx moment: “I can’t believe they let me into this place.” 🙂

The Meetings

The meetings, however, were a different story. While all the externals of this event were spectacular, the content of the meetings was less than pedestrian. The presenters dressed well and tried to use impressive words. The PowerPoint slides were perfect, but the actual content was… lame. A local VFW or Women’s Auxiliary could have done as well.

I heard one speech – in the impressive ‘headphone’ amphitheater – where the speaker said that vast areas of her home country would be entirely underwater in ten years (which would have been 2009) and that every soul living there would be dead. As evidence, she referred to impressive names and organizations, who had “said so.”

And that was the way the whole conference went. The ‘science’ of one group referred to the ‘science’ of another, then another, and then still another, who referred back to the first! Intellectually, the entire show was a sham. I kept thinking that there had to be someone there who was competent, that perhaps they were having the real meetings in some back room somewhere. If so, I never found them, and I had what appeared to be free run of the place.

The Test

There’s a little test that I run in my mind in cases like this. I ask myself: If I owned a convenience store, would I feel good about having this person manage it for me when I was out of town for a week?

I applied my test to the entire assemblage of impressive-looking people at this event. There was only one person that passed, and that man was a Dutch journalist, not involved with the UN or any of its orbiting NGOs.

As best I could tell, nearly every person at this event was someone making a living from global warming, or some official’s son, daughter, brother-in-law, or cousin. I found none that had any real substance. They were flying first class, staying at magnificent hotels, eating in the finest restaurants, and, as I later learned, hiring the best local prostitutes.

And they were doing it all on some government’s tab.

I was able to get my hands on some of the UN’s internal documentation (which I’ve since lost, sadly). It showed that nearly every dollar they had spent on global warming – and it was many, many millions – was spent on meetings. Of course, they used lots of fancy euphemisms for “meetings,” like “plenary sessions.”

There were two primary types of officials present: those from the big states, who were looking for a new bureaucracy to run, and those from the small states, looking for a handout.

In the End

My thoughts while walking away from these meetings were these:

If, tomorrow, new research emerged, proving beyond any shadow of a doubt that global warming was false, these people would not be ashamed. Rather, they’d stand up, look around at each other, and say, “Well, what should we do next?”

As I’ve mentioned before, the people who are trying to run the world are not smarter than you. My experience at the UN is part of what led me to that conclusion.

Paul Rosenberg

http://www.freemansperspective.com

No the people that run the world are not smarter than us and that is why I am trying to spread power from them to the rest of the people.

Power corrupts. It will bring them down without my interference.

Also the UN is full of politicians and NGOs, not scientists. But surveys of climate scientists say that between 80% and 95% of them beleieve that humans (not volcanoes which are a natural phenomenon) are changing the earth’s climate.

John, let me reiterate: It isn’t climate change that worries me, but rather climate-change hysteria in the age of statism that I find ominous. You see, whether stated outright or unstated but understood, it is the position of some 80 to 95 percent of those declaiming on the disastrous future consequences of anthropomorphic global warming “if something isn’t done,” it will mean apocalypse, and the something can only be done by government. If government is given authority to ameliorate climate change, I know it will only make matters worse. Who will we put in charge of saving us? The post office, EPA or TSA? If you want a real environmental disaster, put government in charge of the climate.

The government is already in charge of the climate. The question is what are they going to do with their power. Many of us are trying to get the government to not steal land from farmers and indigenous people so they can build pipelines to transfer tar sands across the country. And trying to get the government to not authorize fracking in watersheds that feed cities.

As you pointed out taxes are everywhere. Why not influence what gets taxed?

As bad as government is, climate change is worse. We are probably causing a mass extinction already and climate change will accelerate it. What is your solution?

John, I would have to accept your conclusions that climate change is worse than government, and that “we” are probably causing a mass extinction already and climate change will accelerate it. I don’t accept. The most likely cause of a mass extinction that looms on the horizon is an accidental or intentional exchange of nuclear weapons by the governments that control the nuclear arsenals. And please don’t tell me the science is settled. It isn’t. The fact that climate hysteria uses the “its settled,” pejorative to silence the opposition tells me above all other considerations that it isn’t settled and the scientific arguments are perforated with weakness that are better not exposed to criticism. But right or wrong, all the histrionics is directed on persuading government to “just do something,” do it with other people’s money, of which some will stick to the backers of climate hysteria scientists and the rest–a never before seen expenditure of OPM–will be wasted and do more damage than good. Nothing good comes from violence (this site is dedicated to nonviolence, isn’t it), and government only operates by violent means. Love = liberty. The Golden Rule precludes governments and rulers. The Great Commandment, love your neighbor as yourself, precludes taxation.

What about just getting government to stop doing bad things with other people’s money, like subsidizing oil companies, using eminent domain to clear the way for pipelines, forcing people to accept fracking pads on their property, using the military to make the world safe for big oil, etc.?

John asked, “What about just getting government to stop doing bad things with other people’s money, like subsidizing oil companies, using eminent domain to clear the way for pipelines, forcing people to accept fracking pads on their property, using the military to make the world safe for big oil, etc.?”

I’d go along with all of those improvements–if they were possible, but I do not believe they are. The problem, which explains all of those bad things government does, is the nature of government. I buy the aphorism: “a bad tree cannot bear good fruit,” also phrased, “nothing comes from corn but corn, nothing from nettles but nettles,” and several other variation of the same verity. Government utterly depends on the initiation of violence. Violence begets only violence, you cannot expect anything good to come from it. I’d rather my child became a pickpocket than a politician or government agent.