After Tunisia’s nonviolent revolution, on March 15, 2011, citizens of the small southern Syrian city of Duraa organized to challenge the government’s severe torture of 20 children, who had posted graffiti criticizing the government. As news spread of the authorities’ crushing of the civil resisters who objected to torturing children, sympathetic demonstrations swelled in solidarity across much of Syria. Local pro-democracy movements dropped ping-pong balls with “Freedom” and “Democracy” written on them from hillsides into towns below. Fountains sprayed red-tinted water, in allusion to gratuitous killings. The increasing brutality raised the voices of Syrians, who minimally asked for protection of civilians. Person by person, family by family, community by community, Syrians turned against the government of Bashar al-Assad. They changed sides.

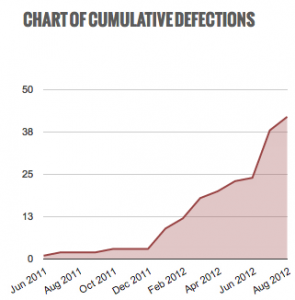

More recently, a steady trickle of members of the Syrian military forces and political elite have been defecting as well — the latest and most pronounced example being Prime Minister Riyad Farid Hijab, who fled with his family to Jordan in the early morning of August 1. In July, 85 members of the Syrian military, including a general, defected to Turkey. At a refugee camp, they joined some 2,000 former soldiers and ranking officers who had already abandoned their loyalty to Bashar. In late June, another general, two colonels, a major and a lieutenant were part of a group of 33 soldiers and brass who sought refuge. A few days before, a Syrian air force pilot, both a colonel and squadron commander, defected by commandeering a Russian fighter aircraft for Jordan, while Syrian sources said that eight Syrian pilots had also traveled overland to reach Jordan.

Al Jazeera has produced a tool for visualizing the defections occurring in Syria, which displays the diplomats, ranking military officials, members of parliament and others who have rejected allegiance to Bashar.

These defections are part of a sequence of violent and nonviolent conflicts that began in earnest last April. Although Syria’s struggle started with nonviolent mobilization, parallel movements are now operating with an underground nonviolent mobilization and an armed wing. After lifting the country’s decades-old state of emergency enacted by his father last spring, Bashar sent tanks into uneasy cities as the security forces meant to protect Syrians opened fire on markedly unarmed contenders for democratic change. This was the first of a succession of brutal crackdowns in the intervening months, which have continued to escalate. It is an old trick to use harsh reprisals in an effort to provoke intentionally nonviolent civil resisters into a violent response, thereby creating pretexts for still more cruel retribution. More than 21,000 are now estimated to have died at the hands of Bashar’s carmine regime.

Most of the defectors thus far have been Sunni Muslims and are breaking ranks from a regime dominated by the Alawite minority, which represents only 13 percent of Syria’s population, including the Assad family. Even if Bashar were to step aside, his system is largely made up of Alawites, whose associates might continue their fighting and retaliate. Former Prime Minister Hijab recently said from Jordan, “Based on my experience and my position, the regime is falling apart morally, materially, economically. … Its military is rusting, and it only controls 30 percent of Syria’s territory.” He suggests that numerous senior civilian and military officials in Syria, whom he called “leaders with dignity,” are waiting to defect.

Once a mobilization is able to sway the loyalties and allegiances of the personnel who work for a society’s leading institutions, its odds of success increase. When movements confront seemingly invincible despotic regimes, or are in the concluding phases of a civil-resistance campaign, a decisive development can be to win over the armed forces, security apparatus or civilian police. The military and security forces may not even assertively support the movement or its objectives. What counts is whether they, as bulwarks of the regime or target group, feel alienated, hope for a new government, become disgusted with their own collusion with a cruel administration, or become unwilling to follow orders to kill or wound their fellow citizens. They also may fear subsequently being held accountable for having committed atrocities.

Can such defections be stimulated or prodded? Nonviolent discipline, for one thing, appears to help. The data of political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan suggest that large campaigns evincing a commitment to nonviolent resistance have a higher likelihood of producing defections from within the security apparatus. They found that successful violent campaigns saw defections occur approximately 32 percent of the time, while successful nonviolent campaigns experienced defections about 52 percent of the time.

Some movements have consciously adopted a policy of fraternization. By this we mean, literally, brotherly or friendly behavior, searching for sympathizers, and outreach to police, soldiers and security — potentially alienating the loyalties of state servants from repugnant policies or regimes. Music and culture may be shared by police, security services and military troops, and can therefore play a part in such fraternization.

In Ukraine, starting at the close of 2002, opposition leaders reached out and contacted retired army officers and middle-level members of the army to discuss possible future support. The national mobilization of citizens challenging electoral fraud would lead to a peaceful handover of power in 2004–2005.

When, almost a year ago, I wrote about the importance of defections from the Syrian military in “Overcoming the Defection Barrier in Syria,” I described the ouster of President Eduard A. Shevardnadze of Georgia on the Black Sea, who in 2003 was deposed by a popular movement. Its protagonists fraternized with the police and army, offering sandwiches and placing flowers in the soldiers’ gun barrels. The police did not fire when demonstrators overran the parliament building.

With the infinite historical variety of civil resistance, a mobilization, particularly one with the tragic consequences that we’ve seen in Syria, defies formulaic answers. What might have been beneficial a year ago may be futile now. Yet recent defections of Syria’s top military ranks and commanding officers suggest that Bashar and his regime have been losing the fealty and cooperation of members of one of its most important bulwarks of support.