Something about the campaign against the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline that inspires me is that the organizers refused to accept that the fight was over. Beginning with front-line groups in Alberta, Canada, where the indigenous were expected to knuckle under and accept yet another abuse of their land, tradition and families, group after group stubbornly refuses to comply.

In the United States, Nebraskan ranchers and young anarchists and white-haired environmentalists are only some of the groups that won’t go along with the outrage. NASA climate scientist James Hanson has reported that, if the tar sands are fully exploited, it’s “game over” for the climate. Seventy-five thousand people and counting have pledged civil disobedience if President Obama agrees to the pipeline that is planned to carry tar gunk from Alberta to Gulf Coast refineries and then off to the rest of the world.

In 2011 it seemed that the pipeline was all but approved by the White House, going along with a corrupt State Department recommendation written by consultants for TransCanada, the Koch brothers and others who profit from planet-destruction. Now, major investors in the pipeline believe they see the handwriting on the wall; Storebrand, one of the oldest and largest insurance companies in Norway, just announced it is pulling out of the project because it is a bad investment.

Those of us in the struggle know we haven’t won yet, but we have a fighting chance. How is it that people at the grassroots can succeed in undoing a done deal?

Don’t trust the politicians

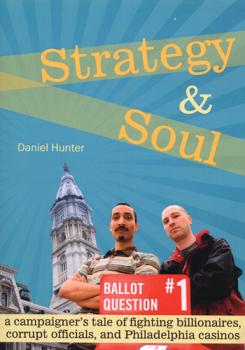

In Daniel Hunter’s new book Strategy and Soul, we can see unfolding a methodology that gives hope to the grassroots activists in the United States and Europe who are losing battles in the escalating class war on both sides of the Atlantic. Daniel’s writing is unique because he’s so honest about what it’s like to fight uphill, especially when working with people who aren’t self-identified activists and who may lose heart when they hear that the fix is in.

In Daniel Hunter’s new book Strategy and Soul, we can see unfolding a methodology that gives hope to the grassroots activists in the United States and Europe who are losing battles in the escalating class war on both sides of the Atlantic. Daniel’s writing is unique because he’s so honest about what it’s like to fight uphill, especially when working with people who aren’t self-identified activists and who may lose heart when they hear that the fix is in.

He tells in revealing detail about the relationship between his campaign and assorted politicians — allies, enemies and in-betweens — and helps organizers to see the nuances that enable us to use politicians instead of the other way around. While reading it I remembered a mistake I made as a young organizer in being too rigid with my instinct of distrust, when I nearly turned a City Council ally into an enemy. We reconciled in his hospital room, and I still wince when I remember how I let my ideology trump my careful analysis of what was going on.

I’m not alone in my rigidity, I think; many activists are turned off by people naively believing politicians when they say that something is a done deal, forgetting that it’s the politicians’ job to keep us dependent on them. I find it especially irritating because so many people tell pollsters they don’t trust politicians, only to turn around and trust them in moments of crisis.

Daniel’s narrative — which kept me turning the pages even though I knew the end of the story from personal experience — shows how he, Jethro Heiko, Anne Dicker and others in the heart of the campaign against casinos initiated moves that influenced politicians to reverse themselves and get on the bandwagon. Instead of repeatedly asking the politicians for help, which Jethro called “feeding the monster,” the campaigners got the politicians to come to them.

The crisis that provided the opportunity was the state deciding to impose on Philadelphia neighborhoods huge big-box gambling casinos across the street from houses and schools. Pennsylvania intended to force the city to suffer the crime and economic loss associated with millionaire-operated gambling.

Because state legislators knew how outrageous the plan was, the legislation was passed in the dead of night just before a holiday weekend. Of course, when the neighborhoods heard about it they would protest, but so what? Like so many protests against schools and libraries closing, food stamps being taken away, mountaintops being blown up or a tar sands pipeline being planned, politicians try to pacify the grassroots by assuring them that, sadly, nothing can be done.

The millionaire investors, supplemented by a Chicago billionaire, finally got one Philadelphia casino (one-fourth of its projected size) and are at this writing still struggling to get a second. They spent tens of millions of dollars to fight a barely funded grassroots insurgency.

What makes Daniel’s account a kind of mentor-in-print is that he shows us how to empower ourselves by engaging the power of all three approaches: community organizing, creative direct action, and narrative strategizing. This last element was provided partly by Quebecois activist Philippe Duhamel, one of the architects of the defeat of the Free Trade Area of the Americas — which was once also, according to U.S. politicians, a done deal.

Defense in crisis as an opportunity

Visionary activists have a habit of comparing what is with what ought to be and then acting to make a change. It’s one of our gifts to the world. We may forget, however, that most people are too preoccupied with “life” — job, family, kids, friends — to want to look for new causes to take up their time.

What gets people to prioritize action is when a crisis comes along that invites them to rise to the defense of something they value.

The breakthrough in Daniel’s campaign — taking he and his fellow activists from being a voice in the wilderness to a force to be reckoned with — arose from just such an awareness. Campaigners caught the state’s gambling commission operating in secret and then launched a mini-campaign within their larger campaign, called “Operation Transparency.” They demanded the agency’s files by a set date, they stimulated the interest of the media and politicians by following their own timeline with a series of imaginative actions, and then they attempted a “citizens’ search and seizure” of the documents, earning them arrest and excellent statewide publicity.

People in the threatened neighborhoods perked up. They believed their government should be transparent, and the possibility that it wasn’t disturbed them. Allies came forward from around the city and state, and the campaigners found themselves empowered.

The need to defend fundamental institutions, like public schools, offers a matchless opportunity to move against the 1 percent because it involves masses of people who otherwise will not act. However, the newly-involved enter campaigns full of disempowering messages in their heads, like “trust politician allies” and “it’s not wise to stick our necks out too far” and “protest is about reacting to the opponent’s moves.” Daniel’s phrase for that last one is “ritualizing losing.”

Indeed, without the contributions of community organizing skills, imaginative direct action tactics and a narrative strategy, communities will, most likely, lose. That’s true for the Keystone XL pipeline fight, as well, but the good news about both Daniel’s campaign and the Keystone campaign is that we can see a learning curve.

No more marches or rallies

One way to signal that campaign leadership has run out of ideas is to invite people to a rally or march. For most of us, this is not inspiring. For the media, it’s usually not worth covering. For those reasons Daniel and Jethro made a pact: They would force themselves to be creative by ruling out marches and rallies.

They didn’t see a problem raiding the treasure trove of other movements’ creativity, however. When facing one of their biggest setbacks — the state’s Supreme Court ruling against a Philadelphia referendum on casino — they went to Daniel’s own tradition for inspiration: the civil rights movement. When African Americans in Mississippi were blocked from running candidates in the racist voting system, they ran their own parallel election. The Philly campaign did the same, generating more city-wide support and state-wide allies, and pulling their neighborhood base back from despair.

What puts the “soul” in Daniel’s account, for me, is that the unfolding narrative isn’t glamorized and the actors aren’t larger-than-life. The odds were cruelly against them. They bickered and fought and made mistakes. They felt ignored by the trendy mainstream activist community. They courted burn-out. But then they shared their vulnerability and recovered their hearts, and learned lessons of value to us all.

GEORGE LAKEY REMINDS ME YET AGAIN THAT EACH OF US ORDINARY FOLKS, AWARE OF OUR INCOMPLETE KNOWLEDGE, OUR FEAR OF BEING IMPERFECT, AND OUR SENSE OF BEING ONLY ONE PERSON, CAN STILL JOIN FORCES TO DISARM THE POWERFUL INSTITUTIONS PROFITING FROM WILLFUL AND PROFITABLE DESTRUCTION OF THE QUALITY OF OUR LIFE TOGETHER HERE ON PLANET EARTH. DANIEL’S BOOK CAN ACCOMPANY US AS WE SHOW UP, LEARN WHAT’S GOING ON, SPEAK OUT, MAKE MISTAKES; LEARN MORE ABOUT WHAT’S GOING ON; LISTEN TO OUR HEARTS; LISTEN TO WHAT OTHER’S HEARTS ARE SAYING; FOCUS ON OUR CLEAR GOAL; GET CREATIVE; WELCOME ALL THOSE WHO SHOW UP, HANG IN THERE, MAKE TIME FOR REFLECTION AND FOR CELEBRATION; CHANGE THE STORY; DISCOVER TOGETHER THE ENERGY AND STRENGTH OF GRASSROOTS DEMOCRACY. THANK YOU GEORGE AND DANIEL

Great post George. In my experience vulnerability is core to any good strategy (and great relationships too). Thanks for sharing this and of course to Daniel for his work on the campaign and writing a great book.

I’m still reading Strategy & Soul but agree with George that Daniel’s vulnerability is part of what makes this book special. I love hearing about the moments when he feels anxious but projects calm and his thought process in dealing with difficult situations. I’ll especially remember their decision not to schedule a vigil or event for the day when they expected a major setback, instead insisting on their own timetable and script. Thanks George for spreading the word about this book.

MUCHAS GRACIAS. FELICITACIONES

Thanks for this article, George. It is so pertinent given how often the activist question needs to be “what is to be un-done” – and undone in such a way that it paves the way for actually creating more of what we want. This is one way of thinking about revolutionary reforms, yes?

What really struck me reading this piece, however, was the idea that our “power holder” opponents seem to employ the same technique throughout so many campaigns – the technique of aiming to convince us that RESISTANCE IS FUTILE. Prior to a campaign this manifests in language like “It’s a done deal.” During a campaign, this manifests in their ignoring activists and inviting the media to do the same – (“Nothing to see here, folks”) as long as they can. And if campaigners and organizers have the tenacity to move through those Gandhian phases (“First the ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win”) all the way to victory, the power holders’ last message is “Well, you didn’t really win because a) we didn’t really want to do that thing or b) we changed our minds but it had nothing to do with you.”

The positive take-away comes when we question the lengths to which opponents go to convince us of our lack of power. Why would they do so – unless we are actually far more powerful than we realize? The insight that we have a lot of power and that much of that power rests in our willingness and ability to non-cooperate is central to waging nonviolence. Thus it is not surprising that opponents try to curtail this realization early on.

Fortunately, smart campaigners and organizers (like the folk of CasinoFree Philly) keep creating the conditions for more people to remember that – far from being futile – resistance is actually very fertile indeed.